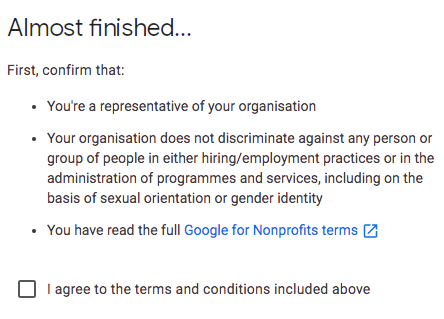

I was busy setting up Google Workspace for Nonprofits for my church when I was confronted by this:

What am I to do?

I turned to Twitter:

OK @Google, we're a church, and that means that some of our staff need to be Christians, so yes, from time to time, we do discriminate - legally! - against non-Christians. Is that OK? pic.twitter.com/lk7scLHSVR

— Anthony Smith (@anthonyjsmith) July 21, 2022

The problem is that there is more than one way to define ‘discriminate’, and it’s all a bit muddled.

Essentially, there are two ways of defining ‘discrimination’: using a descriptive definition, or using a moralised (or normative) definition.

- Descriptive: discrimination is often wrong, but not always

- Moralised/normative: discrimination is always wrong, by definition

The moralised definition seems more widespread, and refers to practices that ‘wrongfully impose a relative disadvantage or deprivation on persons based on their membership in some salient social group’ (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

Clearly, there are ways of treating people differently that are not wrong. For example, if you hire someone who is honest and competent, then, following a descriptive definition, you are ‘discriminating’ against incompetent liars. But this is not ‘discrimination’ in a moralised sense: it is not morally problematic, therefore, by definition, it is not ‘discrimination’.

‘Discrimination’ is usually limited to certain ‘protected characteristics’. The UK Equality Act 2010 lists these as: ‘age; disability; gender reassignment; marriage and civil partnership; pregnancy and maternity; race; religion or belief; sex; sexual orientation’. In general, it is wrong to treat people differently on the basis of these protected characteristics. But there are countless exceptions. For example, the Equality Act states that:

(2) If the protected characteristic is age, A does not discriminate against B if A can show A’s treatment of B to be a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

(3) If the protected characteristic is disability, and B is not a disabled person, A does not discriminate against B only because A treats or would treat disabled persons more favourably than A treats B.

This is an example of the moralised definition in action. In these cases, it is morally (and legally) acceptable for A to treat B differently, and therefore, by definition, it is not ‘discrimination’: ‘A does not discriminate against B’.

This means that, when a religious organisation makes use of the legal exceptions to the general rule, and treats people differently on the basis of their religion, or (in some cases) on the basis of their ‘sexual orientation or gender identity’, this (at least in the eyes of the law) is not problematic, and is therefore not ‘discrimination’.

So which definition does Google use?

Although the terms do not make it explicit, it seems clear that Google is using a moralised definition: to ‘discriminate’ is wrong, by definition. Google does not list the protected characteristics or mention any exceptions. You simply need to confirm that your organisation ‘does not discriminate against any person or group of people’ in employment or the provision of services. This is clearly not intended to include those many cases in which it is appropriate to treat different people differently.

It is also worth noting that, if Google were to make it impossible for the majority of religious organisations to sign up to their terms, that would count as discrimination on the basis of religion, and would therefore presumably be illegal.

If you’re a resident of, or an organization based in, the United Kingdom, these terms and your relationship with Google under these terms and service-specific additional terms, are governed by English law, and you can file legal disputes in the English courts.

So I think it is fair to understand Google to be requiring that your organisation does not ‘discriminate (i.e., unlawfully) against …’.

So I think it’s OK for a law-abiding religious organisation in the UK to proceed with Google for Nonprofits.

(If all of this is correct, then Google’s terms, when applied in the UK, simply mean that organisations must be law-abiding. I suppose things might be different in other countries.)